A couple of pictures from my 'berlin nights' series came up as one of the staff picks for Art Connect Berlin this week.

MAGNUM CONTACT SHEETS

I recently had the pleasure of seeing the 'Magnum Contact Sheets' exhibition at the Amerika Haus, in Berlin, which recently opened its doors once more. It consists of each generation of the Magnum photographers, beginning in the first days when it hurled this collective into our insatiable world, the likes of Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, George Rodger, William Vandivert and David 'Chim' Seymour, in 1947. Since its birth, it lists some of the greatest twentieth century photographers as its members, many of which are shown at the exhibition, as the viewer is confronted with over a hundred contact sheets, shown beside one or two of their final, and known, pictures. Little snippets of words, of memories, or recollections from the photographer accompany each contact sheet exhibited.

At first, for me, it slightly dispelled Bresson's philosophy of 'the decisive moment', as his contact sheet revealed him moving around his subjects, snapping, looking for the right angle, snapping, sidestepping, snapping, trying to find the right position from which to take the picture from, which were many in number upon that roll of film (it was the picture of children playing in Seville, in Spain (1933), with a boy on crutches in the foreground). But the more one looked at it, and at the many others in this exhibition, one started to have the feeling of something so intimate being revealed by the photographers who were shown. It illuminated, however subtly, the thought and instinct that took place in those decisive moments leading up to that single point in time when it all happened, when it suddenly snapped together in an instant in which the picture was taken. Once this perception replaced my initial one, it became a whole other experience in which to view it all from, where it suddenly opened up other layers and thoughts in reaction to these photographs, and there were so many good ones.

A good photograph can create a kind of harmony within the frame that we look into, and can, on rare occasion, steal our breath from our exhaling lungs (harmony through form, composition, placing of people, subtext, history, meaning, metaphor, and everything else that goes with a good picture). And we know these pictures, many of them, for they have become immortalised, in a way, within the collective psyche, part of that canon of pictures that seem to resound no matter how old they are or in what country they were taken in. They can speak a sort of truth, of what it means to be human and alive and filled with hopes and fears, of horror, but of beauty, also, which can sing amidst the chaos of this earth in which we walk within. And so we search for these types of pictures, consciously or unconsciously, looking for the ones that can stop us dead, that can speak to us and say something about the human condition, of our place in this mad, mad world. It has been with us for around 32,000 years, that intrinsic need to make art, to communicate with the world outside of our selves, as was once done in the Chauvet Cave, in southern France, which contains some of the oldest images painted by humans.

And then, almost halfway through the exhibition, and bringing me, momentarily, out of my reverie and into a smile, were the words by Abbas, which were written onto the wall opposite a contact sheet of Margaret Thatcher (shot during the 1980 Conservative Party conference):

'A contact sheet reflects not only what the photographer sees and chooses to ... but also their moods, their hesitations, their failures. It is pitiless.'

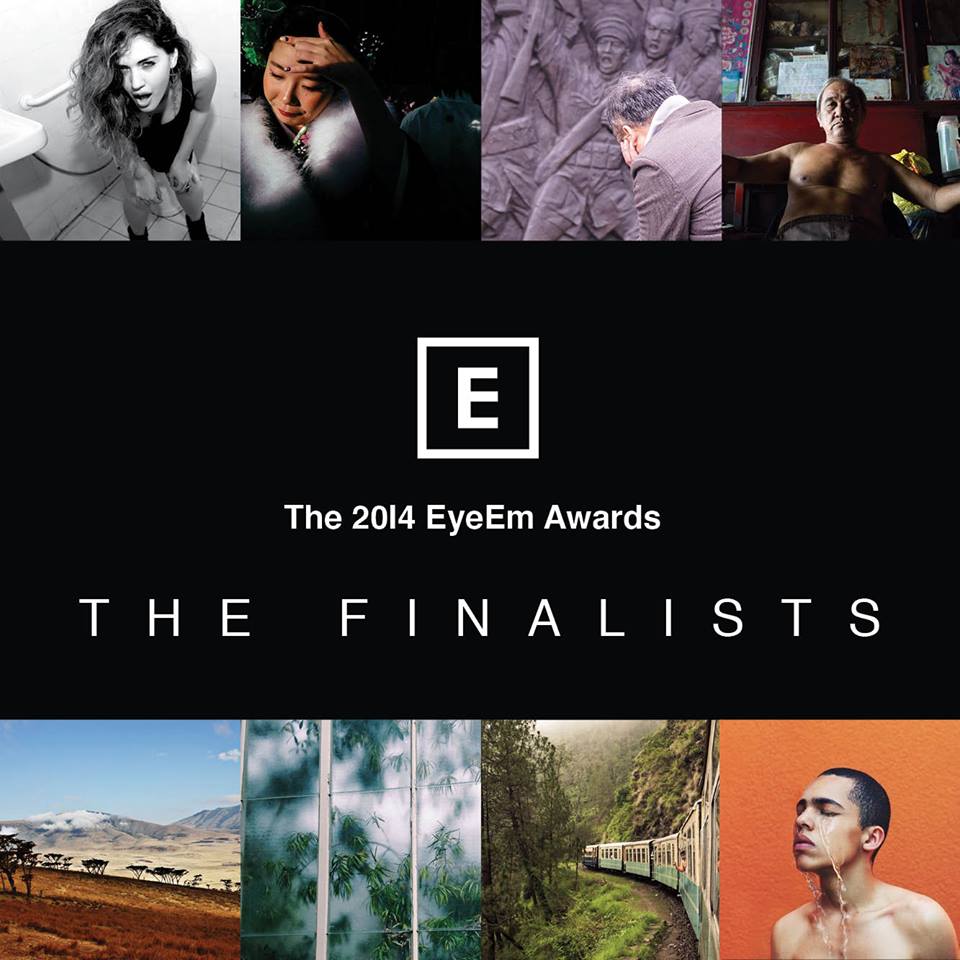

EyeEm FINALIST

Out of 100,00 pictures submitted for the EyeEm photo competition, I was shortlised to the final 100, which was a pleasure to be a part of. Their full listing can be seen here.

DAIDO MORIYAMA PHOTOGRAPHY TALK

'Everyone has desires. The quality and the volume of those desires changes with age, but that desire is always serious and real. Photography is an expression of those desires.'

― daido moriyama

STEPHEN SHORE PHOTOGRAPY TALK

A short little interview with Stephen Shore, who along with William Eggleston, pushed colour photography into our visual language as an accepted form of expression - Eggleston was experimenting with color in 1965 and 1966 whilst for Shore it was in 1972.

Here, Shore talks briefly about how he got into photography, of shooting in Andy Warhol's factory, as this film's director, Heidi Hartwig, aims to 'dispel the mystery of the man behind the mythology'. And all in four minutes.

PHILLIP-LORCA DICORCIA PHOTOGRAPY TALK

The photographer Phillip-Lorca diCorcia talks about this work through pictures, throughout the years of 1975-2012, and his various projects shot during that time.

JEFF WALL TALK

“My work is a reconstruction and reconstruction is a philosophical activity. If I can create a drama that has philosophical meaning, that’s fine, or sometimes, it is not from meaning but a reconstruction of a feeling. It is best to capture in a photograph a feeling, an emotion, a look, a memory, a perception or a relationship.”

- Jeff Wall

An interesting interview with Jeff Wall, as he talks about the construction of his photographs, of their size, their magnitude, and how he envisions them.

INSIDE OUT: THE PEOPLE'S ART PROJECT

'In 2011, French street artist JR announced his TED Prize winning wish to connect people worldwide through a collaborative artistic action. He launched INSIDE OUT, inspiring thousands of people — from South Dakota to Iran — to collectively transform their personal identities into public artwork. From Moscow to Tunisia, citizens have turned more than 120,000 digital portraits into bold posters covering everything from city walls to trains.'

- TED

THE AFRONAUTS

The highlight for me at this year's Deutsche Borse Photography Prize was the project 'The Afronauts', from Cristina De Middel. It is based on the remarkable, and pretty unknown, story of the 1964 Zambia space program, which wanted to send the first African astronaut to the moon.

FRANCESCA WOODMAN

Meet the Woodmans, a family of artists including their late daughter Francesca Woodman, best known for her self-portraits. This is an interesting insight into her creative outpouring before her premature death, and of how her photography grew to be loved in her passing, which still resounds and influences people today.

LEICA PORTRAIT: JOEL MEYEROWITZ

Joel Meyerowitz, one of the great street photographers of the twentieth century, talks about his time watching the photographer Robert Frank taking pictures ("and it was all so physical, balletic and magical"), to his own time, shooting for over 50 years, with most of his work being shot in New York. He explains his views on photography as well as his need to get into Ground Zero, after 9/11, to document the wreckage of the Twin Towers being cleared, where he shot for nine months.

A FILM BY WILLIAM KLEIN

A hypnotic, evocative film of Times Square, in 1958, as shot through the cinematic lens of the American photographer William Klein, titled 'Broadway by Light'.

GREGORY CREWDSON DOCUMENTARY

This week I saw the Q&A with the director of the documentary 'Close Encounters', a film about the American photographer Gregory Crewdson. In this informative piece, we are shown the cinematic scale of his photographic shoots, where we see the anxiety, the loneliness and paranoia of people. Inside each carefully, obsessively composed scene, we glimpse some of the secrets we, as a people, hold deep within ourselves; of its heaviness, pulling its character down under the weight of its own matter.

And, like the painter Edward Hopper (clearly one of his biggest influences), we see the disconnection, the gulf that exists between people, of the essential aloneness of what it is to be human; where we are born, live and die alone within the central nature of our being, viewing the world outwards, from our own perception and sense of self.

Most of Gregory Crewdson's work is shot at twilight, where the light takes on another quality; something mysterious, mesmerising, an otherworldly feel. If it is not shot at magic hour, then it is taken at night, where dreams and nightmares crash together, enveloping each scene in a world that resembles David Lynch's 'Blue Velvet' - a dark, ugly underbelly seething from under the surface of the gardens, surrounded by their white picket fences of superficial normality. And, like Edward Hopper, we are shown moments where something dramatic, out of the ordinary, terrifying even, has taken place, or is about to burst into being. With his pictures we are left with the realms of our imagination to fill in the blanks, where his imagery burns itself into the inside of our minds like a laser, etching itself vividly on the backs of ones eyes - the detail so sharp, so rich and textured, unsettling.

His images are like nothing else I have seen in photography, something so much closer to a Hitchcock movie; a peeling back of the surface, a revelation to the suffering of psychology within this fragmented world, where we seem to stand together, and yet so apart. We know one another, but are strangers at the same time. This is a place where secrets take form in an exterior world, manifesting from secrets and fears, and where each frame is fixed onto large format film - and there, within his work, we catch a glimpse into the frailty of modern existence, of what it is to think and to despair, to be afraid and cut off from the essential unity of life and matter.

VBS PICTURE PERFECT: CHRISTOPHER ANDERSON

"Emotion or feeling is really the only thing about pictures I find interesting. Beyond that it is just a trick."Christopher Anderson

Beautifully intimate, close, tender, revealing, Magnum photographer Christopher Anderson reveals interactions; moments of people with other people, framed within with their chosen landscape, which becomes a kind of extension of them, as they seem to burst within the frame, making so much noise and yet, at the same time, they can be so quiet, gentle, meditative.

BONAKDAR CLEARY NOW REPRESENTS THE PHOTOGRAPHER NICK BALLON

My dear friend, and mentor, Nick Ballon, has recently had the news he'll be represented by Bonakdar Cleary, along with six other fantastic photographers. You can see a selection of Nick's work on their website, here.

TOM WAITS NARRATES THE LIFE OF JOHN BALDESSARI, IN 6 MINUTES

Tom Waits narrates John Baldessari’s life, compressed into six minutes of film, which rushes through with a smile to the 'William Tell Overture', by Rossini.

The epic life of a world-class artist, jammed into six minutes. Narrated by Tom Waits. Commissioned by LACMA for their first annual "Art + Film Gala" honoring John Baldessari and Clint Eastwood.

directed by Henry Joost & Ariel Schulman (http://gosupermarche.com/) edited by Max Joseph (http://www.facebook.com/mjosephfilm) written by Gabe Nussbaum (http://www.bankstreetfilms.com) cinematography by Magdalena Gorka (http://magdalenagorka.com/) & Henry Joost produced by Mandy Yaeger & Erin Wright

Thank you to John Baldessari and his studio. (http://www.baldessari.org/)

"Look at the subject as if you have never seen it before. Examine it from every side. Draw its outline with your eyes or in the air with your hands, and saturate yourself with it."

-John Baldessari

TED: TARYN SIMON PHOTOGRAPHY TALK

TED: "Taryn Simon captures the essence of vast, generation-spanning stories by photographing the descendants of people at the center of the narrative. In this riveting talk she shows a stream of these stories from all over the world, investigating the nature of genealogy and the way our lives are shaped by the interplay of many different forces.

TED: "Taryn Simon captures the essence of vast, generation-spanning stories by photographing the descendants of people at the center of the narrative. In this riveting talk she shows a stream of these stories from all over the world, investigating the nature of genealogy and the way our lives are shaped by the interplay of many different forces.

With a large-format camera and a knack for talking her way into forbidden zones, Taryn Simon photographs portions of the American infrastructure inaccessible to its inhabitants."

"Archives exist because there's something that can't necessarily be articulated. Something is said in the gaps between all the information.”

Taryn Simon

GOD'S LAKE NARROWS: A FASCINATING INTERACTIVE PROJECT

Here is a wonderful example of an interactive, photography and video project by the Canadian artist and filmmaker Kevin Lee Burton, titled 'God’s Lake Narrows'.

Here is a wonderful example of an interactive, photography and video project by the Canadian artist and filmmaker Kevin Lee Burton, titled 'God’s Lake Narrows'.

Here is what the New York Times wrote about it:

"The impetus for 'God’s Lake Narrows' — a personal, multilayered story produced by Canada’s publicly financed National Film Board — was the notion that few people aside from Mr. Lee Burton can envision a “classic northern town.”

It’s very much a question of access. “If you’re in New York,” Mr. Lee Burton, 32, says in the interactive, “you’d be 3,156 kilometers away from God’s Lake. All things considered I’m going to bet you’ve never visited.”

With virtually no economy, the reserve depends heavily upon the government for financial support. Because of the shortage of housing, he and his family shifted from one home to the next, living with relatives. School stopped at the ninth grade. At 15, Mr. Lee Burton — who was born to a Cree mother and a white father — had no choice but to move south to attend public school.

“God’s Lake Narrows,” which was created and produced by Mr. Lee Burton and a sizable team, tries to break down the stereotypes often associated with native reserves."

THE PHOTOGRAPHY OF PAUL GRAHAM

One of the photography shows I regret missing last year was that of Paul Graham and his 'mid-career retrospective' at London's Whitechapel Art Gallery, of which the following piece of writing, written by the gallery itself, is worth quoting for an insight into his work.

"Through renowned photographic series such as the A1, Troubled Land, New Europe or American Night British artist Paul Graham presents vivid portrayals of people and places. This comprehensive survey of over 25 years of work demonstrates his innovative approach to documentary, reinventing traditional genres of photography to create a unique visual language.

In the early 1980s Graham transposed the American genre of the road trip, exemplified by artists such as William Eggleston, to the less glamorous terrain of Britain’s A1 revealing its unexpectedly cinematic potential. He has gone on to use journeys – across Europe, Japan and America – to immerse himself in the landscapes and unconscious rituals of societies. The everyday scenarios he reflects are also embedded with a complex iconography. The hand that an immaculately made up Japanese girl waves across her mouth evokes a society anxiously over-invested in surfaces; under a hot grey Pittsburgh sky, an African American gardener mows the grass verge of a car-park, traversing back and forth, going nowhere.

Arrestingly beautiful, Graham’s photographs transform the banality of a social security office or a suburban lawn into compelling scenes. Yet for all the immediacy of his saturated colours and large formats, these pictures are also about what cannot be seen. ‘I realised that concealment… has run through… my work, from the landscape of Northern Ireland, and the unemployed tucked away in backstreet offices, to the burdens of history swept under the carpet in Europe or Japan. Concealment of our turmoil from others, from ourselves even’. This definitive show includes over 100 photographs as well as Graham’s book works and is accompanied by a comprehensive monograph."

Paul Graham from white tube on Vimeo.

Peter MacGill discusses the work of photographer Paul Graham.

Paul Graham has also written a couple of interesting pieces on his website, one of which I would like to share with you, below, which puts forth an interesting perspective on how a lot of photography is not championed by the art world due to a complexity that is not always easy to sum up in a single sentence..

'The Unreasonable Apple' Presentation at first MoMA Photography Forum, February 2010

This month I read a review in a leading US Art Magazine of a Jeff Wall survey book, praising how he had distinguished himself from previous art photography by:

“Carefully constructing his pictures as provocative often open ended vignettes, instead of just snapping his surroundings”

Anyone who cares about photography‘s unique and astonishing qualities as a medium should be insulted by such remarks, especially here in 2010, in this country, in this city, which has embraced photography like no other.

Now this is maybe just an unthinking review, but what it does illustrate is how there remains a sizeable part of the art world that simply does not get photography. They get artists who use photography to illustrate their ideas, installations, performances and concepts, who 'deploy' the medium as one of a range of artistic strategies to complete their work. But photography for and of itself - photographs taken from the world as it is - are misunderstood as a collection of random observations and lucky moments, or muddled up with photojournalism, or tarred with a semi-derogatory ‘documentary’ tag.

This is tremendously sad, for if we look back, the simple truth is that the majority of the great photographic works of art in the 20th century operate in precisely this territory: from Walker Evans to Robert Frank, Diane Arbus to Garry Winogrand, from Stephen Shore travelling across America in Uncommon Places; Robert Adams navigating the freshly minted suburbs of Denver in The New West, or William Eggleston spiralling towards Jimmy Carter’s hometown in Election Eve, nobody would seriously propose that these sincere photographic artists were merely “snapping their surroundings”.

So what is the issue? The broader art world has no problems with the work of Jeff Wall, or Cindy Sherman or Thomas Demand partly because the creative process in the work is clear and plain to see, and it can be easily articulated what the artist did: Thomas Demand constructs his elaborate sculptural creations over many weeks before photographing them; Cindy Sherman develops, acts and performs in her self-portraits. In each case the handiwork of the artist is readily apparent: something was synthesised, staged, constructed or performed. The dealer can explain this to the client, the curator to the public, the art writer to their readers, etc. The problem is that whilst you can discuss what Jeff Wall did in an elaborately staged street tableaux, how do you explain what Garry Winogrand did on a real New York street when he ‘just’ took the picture? Or for that matter what Stephen Shore created with his deadpan image of a crossroads in El Paso? Anyone with an ounce of sensitivity knows they did something there, and something utterly remarkable at that, but... what? How do we articulate this uniquely photographic creative act, and express what it amounts to in terms such that the art world, highly attuned to synthetic creation -the making of something by the artist- can appreciate serious photography that engages with the world as it is?

Now, please do not get me wrong, I admire the work of Cindy Sherman and Jeff Wall and Thomas Demand - I have zero problems with it, and it is emphatically not an either/or situation. Nor should you misunderstand me in the other direction: I am not arguing for some return to photographic fundamentalism of Magnum style Leica reportage 35mm black & white work or whatever - far from it, for we are clearly in a 'Post Documentary' photographic world now. Both of these disclaimers not withstanding, I have to say that the position of ‘straight’ photography in the art world reminds me of the parable of an isolated community who grew up eating potatoes all their life, and when presented with an apple, though it unreasonable and useless, because it didn’t taste like a potato.

Am I ‘Tilting at Windmills’ here? Perhaps so, but as with the great Don – Cervantes that is – it is to make a point, earnestly, yet with good humour. The point is certainly not the art world versus the photography world, because it is not apples or potatoes, anymore than it is sculpture or painting. The point is that we need the smart, erudite and eloquent people in the art world, the clever curators and writers, those who do get it, to take the time to speak seriously about the nature of such photography, and articulate something of its dazzlingly unique qualities, to help the greater art world, and the public itself understand the nature of the creative act when you dance with life itself - when you form the meaningless world into photographs, then form those photographs into a meaningful world.

Thankfully, as the glass clears, it has become apparent just what an incredible achievement Robert Frank or Garry Winogrand or Diane Arbus or Robert Adams accomplished back in the 50’s, 60’s or 70’s, and for that we must be grateful. For the great exhibitions at the Met, the Whitney, the Guggenheim, and of course MoMA itself; for the books, the catalogues, the enlightened essays: I thank you. But... what of those who work today with equal commitment and sincerity, using straight photography in the cacophonous present? I will not name names here, but for these serious photographers the fog of time still obfuscates their efforts, and the blindness j’accuse some of the art world of suffering from, narrows their options. It means their work will almost never be considered for major exhibitions like Documenta, or placed alongside other artists in a Biennale, or found for sale in high level contemporary galleries and art fairs. This does not just deprive the public of the work, and the work of its place, it denies these artists the self-confidence that enables them to grow, to feel appreciation and affirmation, not to mention some modest financial reward allowing them to continue to work. It is also, most importantly, seeing the world of visual art in narrow terms. It is seeing the apple as unreasonable.

So, what is it we are discussing here - how do we describe the nature of this photographic creativity? My modest skills are insufficient for such things, but let me make an opening offer: perhaps we can agree that through force of vision these artists strive to pierce the opaque threshold of the now, to express something of the thus and so of life at the point they recognised it. They struggle through photography to define these moments and bring them forward in time to us, to the here and now, so that with the clarity of hindsight, we may glimpse something of what it was they perceived. Perhaps here we have stumbled upon a partial, but nonetheless astonishing description of the creative act at the heart of serious photography: nothing less than the measuring and folding of the cloth of time itself.

EDWARD BURTYNSKY ON MANUFACTURED LANDSCAPES

"Accepting his 2005 TED Prize, photographer Edward Burtynsky makes a wish: that his images -- stunning landscapes that document humanity's impact on the world -- help persuade millions to join a global conversation on sustainability.

2005 TED Prize winner Edward Burtynsky has made it his life's work to document humanity's impact on the planet. His riveting photographs, as beautiful as they are horrifying, capture views of the Earth altered by mankind."

-TED